Tags

Creative Obsolescence, Dialogue, Exponential Creative Development, Final Draft, generative AI, haydon, Keats, malcolm X, Margaret Atwood, storytelling, The Bard, The Immortal Dinner, Wordsworth

On the night of December 28th, in the year 1817, B. R. Haydon – by all accounts a rather eccentric British painter – gave a dinner party in his painting room in London. He invited, among others, three of the greatest writers of the age: the poets John Keats and William Wordsworth, and the essayist and wit Charles Lamb. Over the course of a long winter evening, they recited poetry, indulged in the high art of conversation, punctuated with antics both ridiculous and absurd. The evening was filled with such displays of brilliance and wit that Haydon’s party came to be known as The Immortal Dinner.

In a podcast conversation recently with Maryrose Lyons from the Institute of AI Studies, I entered the conversation ostensibly as ‘an endangered species’ – the creative writer in an increasingly AI driven world. In a very pleasant and robust conversation with Maryrose, I ventured some of the ways in which writers can change their lens on AI, and understand more clearly how they can use it as a ‘buddy’ or tool. So with Haydon’s Immortal Dinner in mind, I thought I’d share where our conversation netted out .

Firstly, on that Endangered Species thing, if we listen to the AI doom-gong of some, my professional life is apparently all but over.

AI will not only eat mundane repetitive production line and back-office tasks by the gazillion – it will also consume the flowery likes of me along the way.

Why pay some ink slinger, or hack top-dollar to shape nuggets of written joy either large or small when an algorithm can do all the work at a fraction of the cost? Just think: all those by-lines, pop ups, adverts, blogs, essays, speeches, white papers – and that’s before we even get to the whole teeming slurry pit of marketing content that fills the platforms and networks on which we live – all done without one whining writer or transaction? Pretty compelling really – and it’s a fair cop. Our species are the shapers of the world we live in, so the adage of making beds and lying in them holds true enough. We are the architects of our futures, both good and bad – and sadly, more often than not, it tends to be the bad we focus on most.

The ‘bad’ are not always misguided or hysterical – some perceptions of AI make an interesting point. In conversation with Laird Hamilton, legendary big wave surfer and water man, with whom I co-authored a book called Liferider, he touched on a theory of his that’s worth repeating. His theory is that ‘however good things are’, as a species, we always find a way to mess things up – and that AI is just the next phase in this series of species self -harming. It’s as if, having used our awesome protein computer brains to become the Alpha Predator on the planet, we suddenly realised that we’d created a flaw in the ‘order of things’. We realised that we needed to create a new Alpha Predator to maintain the ecosystem – as if we knew that, without a predator to test us, our evolution would stall in the face of our misuse of all that we’d created. So, we came up with a new predator to ‘thin the herd,’ keep us optimal and maintain the natural order of things. Take a bow, AI.

A powerful idea simply put and not that far fetched.

But.

There are three things that make me believe that, certainly for my shade of the species, extinction of purpose through AI is not a foregone conclusion. But we do need to accept that it will be very bumpy along the way – we live in the times we do.

As Ian McGilchrist pointed out in his book The Master & his Emissary, we are living in a Left Brain Tyranny now. Our seemingly unquenchable desire to use every technology we have, especially our new computational ones, to measure, manipulate and control everything from the universe to human behaviour to shopping basket suggestions is ascendent over the softer humanities and Right Brain creativity. In this world, every human action and task is a cost to be parsed, written down or extinguished in our fetish for ‘best maths homework ever’ – and a pat on the head of course, from whichever ‘teacher’ is marking our homework, whether they be shareholders, CFOs, Investors or simply the person in charge of calculating exco bonuses.

Creative Extinction Rebellion

So, what are these three things that make me think I can survive under, and indeed flourish in the face of this tyranny of AI?

What are the three things that make me believe that ‘creative doers’ like me can evolve and adapt within an AI world and, in real terms, use the ‘enemy’ to elevate and improve themselves, their value and their possibilities along the way?

The first: The Company We Keep concerns the solitary nature of writing, creative exploration, and the absence of creative socialisation. The second, A Bigger Train-set, concerns the Application of one’s creative abilities and the art of evolution. The third, Fuelling the Fire, focuses on the need for AI to be relentlessly fuelled by new creative content and ideas to stay optimal and avoid its own form of endangerment.

So, here are my expanded thoughts on the survival of my breed:

1. The Company We Keep

Creative writers live in an isolated bubble, mostly. Yes, for a period of some 50 years, vast numbers of us of a less purist and more commercial bent sat side-by-side with our art directors and designer cousins in large agency organisations industrialising our crafts, and playing with and executing creative communications of every shade and hue for local and global ‘brands’, organisations or businesses.

Many did this from a rather privileged and well rewarded position. This bright, noisy creative machine exponentially grew under the watchful eye and once bulging bank accounts of advertising, PR, Marketing and Design agencies.

These creatives served the rise of ‘the consumer citizen’ and created a landscape hungry for more of their wares. But the computer age, the internet, mass digitisation, and flexible and remote working has returned many of them to their solitary desks, writing pads and keyboards.

For some creative writers this is bliss. The splendid isolation of it fitted with their ‘lone tortured artist in search of creative pearls’ narrative. But for many, the absence of the serendipitous creativity that existed in socialising their ideas amongst a group of like-minded people every day has narrowed their view’ of the world, their role in it, their craft, and ultimately, the ideas they generate. That’s not good.

At this juncture, many of those writers feel that AI represents just another nail in their creative coffin – the super accelerant of their demise.

But, for me, it offers the opportunity of not only expanding the creative company we keep and bringing the most diverse set of minds to bear on whatever we do, but also seeing our ideas through the eyes and pens of some of the greatest writers the world has ever known, forcing us to raise our bar again and again.

Which brings me to The Immortal Dinner part of the title. In the absence of a set of workmates and a big shared table, we can now use AI to create our own Immortal Dinner, all in the tap of a computer key.

A creative writer can take any creative phrase, description or idea, and feed it into even the most basic ChatGPT with a request to have the phrase rewritten in the words of the likes of Malcolm X, Margaret Atwood, The Bard, Graham Greene, Jumpa Lahiri – anyone that takes your fancy. Five or six goes at that and voila! You have created your own immortal dinner – where your shared idea has been reimagined through the eyes and words of another’s genius. Cheeky? Maybe. Cheating? Not at all.

As an example: to test the edges of a creative concept line I’d developed to explain genomic science in a more compelling, ‘feeling,’ and human way, I invited Jumpa Lahiri, Shabba Ranks, Margaret Atwood, The Bard, JP Donleavy, John Lennon, Iris Murdoch, Bill Bryson, and John Betjemen to my ‘Immortal Dinner.’

The outcome was swift and exhilarating. It opened out other avenues of language and phrasing, and creative thoughts around how different minds, communities, cultures, and eras might see the same thing. It was a dip into the eternal and universal.

Just for fun, I’m going to leave the responses anonymous – see if you can guess which one is which.

My Phrase:

The source code of our humanity.

ChatGPTs responses:

“The intricate design that governs our humanity, subtle yet profound in its influence.”

“The melody that writes our human story, the notes that make us who we are.”

“The quiet script that shapes our humanity, woven into the fabric of who we are.”

“The intricate manual that underpins our very existence, full of quirks and complexities that make us undeniably human.”

“The rhythm and root of our human core, the heartbeat that makes us true.”

“The raw, tangled code that makes us human, messy and marvellous all at once.”

“The blueprint that threads us together as human.”

“The essence that scripts our mortal soul.”

“The very script of our shared human heart.”

So, to summarise the ‘first thing’: For a writer, AI platforms, even the most basic ones, enable creative writers to effectively socialise, hone and explore their creative ideas amongst some very rare company. The machine mind doesn’t provide the answer – but it provides a sophisticated sounding board that enables the writer to ask better questions of themselves and their creativity. What’s not to like?

2. A bigger Train-set

So, to our second point, and AI’s potential to expand and evolve the application of a writer’s craft.

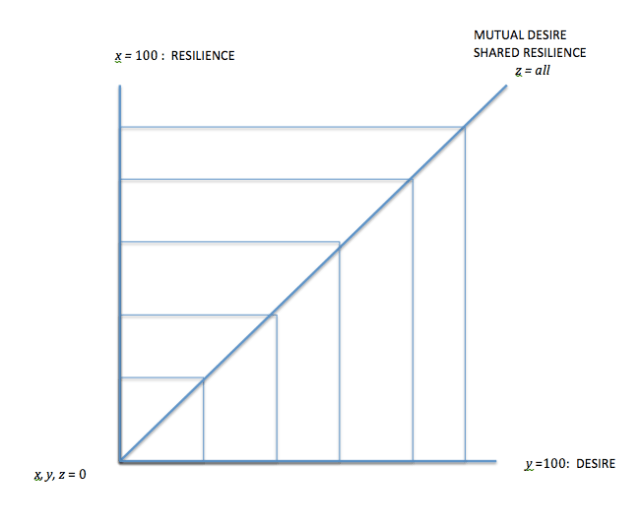

generative AI can help transport a creative writer’s ideas into new channels and skill sets they had otherwise never touched, explored or deemed to be in their ‘wheelhouse.’ This second point focuses on how generative AI can build both commercial resilience and creative possibility at one and the same time.

For example: many commercial writers harbour fantasies of writing a novel or a movie script [though given that Hollywood is in melt down right now, this might be worth shelving for a while at least – Oh, and it’s all AI’s fault.]

Often, the lucky ones will take themselves back to college or, at the very least, embark on a writing course or two. BUT. Both of these options are expensive and time consuming – and if you’re struggling with bills, time poor, or have children or relatives to care for, the luxury of wafting off for a 7-day orgy of self-interested literary self-development, though a very attractive proposition, may well be beyond you. Fear not. ChatGPT to the rescue.

Basic generative Ai platforms can take a rough film treatment of yours [as long as it is well fleshed out, with clear scene structure and well-developed characters], and convert it into a very rough foundation form of Final Draft [a tyranny to those who know it] With one click, you can start to see how your idea falls on the page in script format. Again. It isn’t going to write The Ipcress File for you, or Slumdog Millionaire [unless you ask it to write your script in the style of those films]. The film idea has to be strong first and foremost – otherwise you’re just creating algorithmic ‘noise’

One simple way to test an idea that might be bobbling around in your head is to play with the core idea of it. For example: if your idea is basically Hamlet but played out on a Cruise Liner as a comedy, start by asking ChatGPT to rewrite Hamlet in the style of a sitcom by a TV comedy writer you revere: Armando Iannucci? Sharon Horgan? – take your pick. The result may be madness [but in a way, for Hamlet at least, that would be quite fitting]. This is a simple and quick way of testing an idea to see how much stretch and flex it has in it – and ultimately, whether you still feel excited and enthused enough to put in the leg work to bring it to fruition. The desire and perseverance required to realise an idea fully demands an absolute belief in what you’re trying to do – AI might help tip the balance.

In more particular terms, you can dive into very specific explorations that mix the immortal dinner idea with very particular disciplines to help you to develop voice and tone through comparison. There are a lot of genius screenwriters and their work out there to mine – William Goldman, Elaine May, Joel Cohen, Frances Marion and Tarantino to name but a few. They are masters of their craft and there’s a lot to learn from them. But there are also short cuts where you can test your mettle against them, courtesy of generative AI.

For example: a piece of dialogue from a piece of fiction I’m currently writing features a rather withered and cruel dying mother and her anxious and screwed-up grown-up daughter having a tiff:

“Oh, the whole ‘we named you after a car in a movie’ thing was just a little joke, darling – just for fun.”

“And 40 years of humiliation. Oh, how you must have laughed.”

“Oh, ‘Ren you are soooo dramatic.”

“She puts four ‘o’s in ‘soooo’ and I’m dramatic.”

“Oh, ‘Ren you are soooo funny. You sound just like that American comedian – jewish – Billy something or other.”

“Billy Crystal.”

‘That’s the one.”

Now, I’ve no intention of turning my two provincial English ladies into a pair of gnarly Cali-valley wash-ups perched in a hospice room in a run-down nursing home at the crap end of La Cienaga – but it is interesting to see how the dialogue translates when I put them through a Tarantino lens:

“Oh, c’mon, sweetheart. The whole ‘we named you after a car in a movie’ bit? Just a little gag. You know, for kicks.”

“Yeah, and 40 years of being the punchline. Bet that had you rolling, huh?”

“Damn, Ren, you gotta chill. You’re always soooo extra.”

“She drags out the ‘soooo’ like it’s a freaking opera, and I’m the one overreacting?”

“Ren, you’re a riot. Seriously. You could be that Jewish comedian… Billy, uh… you know the guy.”

“Billy Crystal.”

“That’s the one! Nailed it.”

Again, this is not about answers and the technology doing the work for you. Again, it is a tool by which you can ask better questions of yourself. The examples I’ve used are simplistic, but they are intended to demonstrate one simple point:

Forget what anyone else says about generative AI. Find out for yourself – take control of the technologies available to you and use your creativity to figure out first and foremost how to use them to your advantage. Screw with them, push them. Try to break them. Enjoy the irritatingly good and sometimes great responses they seem to pull out of thin air. Learn something. Surprise yourself. But most of all. Make it fun – and open your mind to everything and anything they have to offer. You’ll be surprised at the outcomes.

Which brings me to the third and last reason for my potentially non endangered species status.

3. Fuelling the Fire

For all the trumpeting of how the exponential improvements of generative AI are going to consume the old creative arts of writing, photography, design, fine arts and most conspicuously, film making, we seem to be missing one simple fact.

Generative AI is capable of doing what it does because of the well from which it draws its responses. It can scrape, curate, reorder, and reassemble all of civilisations current stored intelligence, knowledge, artifacts, systems of thinking and understanding to fit any question or challenge we set it [within reason]. While the well of its enlightenment is being filled with a relentless tsunami of human thought and creativity, it will continue to draw up some remarkable results. But that’s the point. To be the best it can be, the well cannot be allowed to stagnate.

If all human evolution of thought and culture were to stop tomorrow, left to its own devices, AI would eventually eat itself in series of ever-decreasing returns [after a few tries of course, at replicating the sheer individual gloriousness of our far superior protein computing.]

It is therefore not in generative AIs interests that we hang up our creative spurs and accept obsolescence any time soon, whatever the bean-counters may say [though, given how short-term their view is, much like the industries exhausting the natural capital of the planet we exist on, they’d most probably think “screw it’, I’ll be gone by the time that happens”].

We are the fuel. Until the moment comes when AI can replicate the power of that ‘big old protein computer’ we call a brain, and do so a few billion times over, all at once [something that is still a very very long way off], we will always be the fuel of its best performance.

…